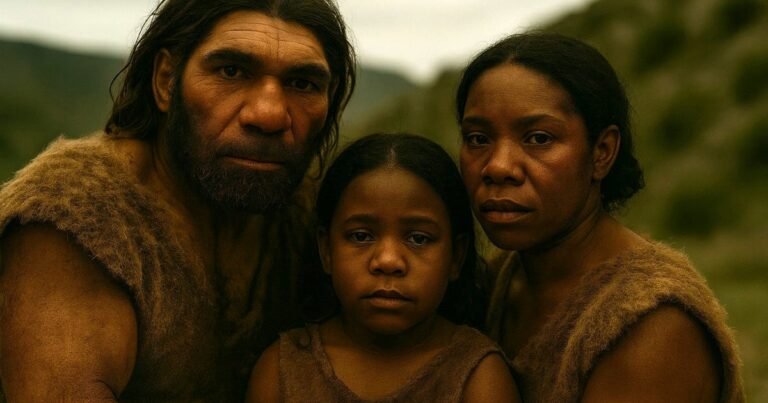

The body of a child found in Skhul Cave in northern Israel from 140,000 years ago changes everything we tend to think about early humans, mainly that they were a horrible lot, says Prof. Israel Hershkovitz of Tel Aviv University, director of the excavation in Skhul Cave with Anne Dambricourt-Malassé of the French National Centre for Scientific Research. Au contraire, early humans and Neanderthals had an attraction and got along beautifully, they hypothesize.

The child of Skhul died at about age 5 and its skeleton was found in 1932. But its classification was confusing to finders Theodore McCown and Arthur Keith, because they noticed it seemed part Homo sapiens and part Neanderthal. Its cranium shape was sapiens, but the lower jaw and inner ear smacked of Neanderthals. Weird! They dodged the difficulty by filing it under a new species, Palaeoanthropus palestinus.

Little palestinus wasn’t an unknown species. It was a hybrid Homo sapiens-Neanderthal, according to a new paper by Hershkovitz and colleagues, published Wednesday in the journal l’Anthropologie. The conclusion is based on its skull morphology.

Neanderthals have been known for around 150 years but were assumed to be brutish ape-people, possibly ancestral to us, but it certainly didn’t occur to anybody that we are part Neanderthal. Now almost a century later we know most of us are mutts and have been for a very long time.

Genetic evidence suggests interbreeding about a quarter-million years ago (though that left markers in Neanderthals, not in us). Then there was a second interbreeding from which we have the child of Skhul from 140,000 years ago: the earliest solid archaeological evidence so far of our interspecies predilections, Hershkovitz says. Among the five other skeletons in Skhul, at least some were also apparently hybrids, he adds.

A third interbreeding event about 50,000 years ago would result in us, but we’ll get to that.

Meet the indigenous people

From our species’ perspective, Neanderthals were here all along. To get to Eurasia, their predecessors had to have crossed the Levant. Evidently, while a group moved onto Eurasia and developed into Neanderthals in the west and Denisovans in the east, some stayed here and didn’t change much.

Primordial Israel had great weather, toothsome megafauna from horses to hippopotami and crocodiles to deer, and local volcanism had died out millions of years earlier. It was all very inviting.

Who was in Israel 420,000 to 200,000 years ago? Them. Pre-Neanderthals, says Hershkovitz. The hominins at Qesem Cave 420,000 years ago were pre-Neanderthals; people at Amud once considered to be “late Neanderthals” returning from Europe have been re-dated to 300,000 years ago and are also now considered pre-Neanderthal. The female of Tabun from 170,000 years ago – same morphology. Nesher Ramla Homo from 130,000 years ago, who was initially assumed to be early modern human but was also the same group, he told Haaretz on Tuesday from yet another hominin cave in central Israel.

So what have we so far? “We show there was a local group of pre-Neanderthals, or Neanderthal-like hominins, who originated in Africa perhaps half a million years ago and evolved here,” Hershkovitz says. “They were the indigenous people.” Not us. They lived here from at least 500,000 to 200,000 years ago.

And what about us?

Enter Species X

When the denizens of Skhul were discovered almost a century ago, the world knew of Neanderthals but assumed they were a primitive human species that we crushed like bugs. Or they assumed this was the ape-man from whom we arose. So the child of Skhul threw quite the monkey wrench into the works in 1935, being nary the one nor the other, not clear Homo sapiens nor Neanderthal.

By now we know there were multiple human species, and we mixed with at least two, Neanderthals and Denisovans. Genetics suggests that our species may have intermixed back in Africa with a more archaic species too. Call it Species X.

Hershkovitz has unusual ideas about Species X.

Our species “left Africa” three times: 250-200,000 years ago, 150,000 years ago and 70-60,000 years ago. Each time, as we advanced, we discovered that the land was not empty. We encountered pre-Neanderthals, and it is not Homo erectus or some other hominin in Africa but they who are Species X, he suggests. They are the unknown species whose DNA some of us preserve to this day.

In this context, we have to mention Kabwe Man aka Broken Hill Man aka Homo rhodesiensis, based on a 300,000-year-old skull found in Zambia that is morphologically indistinguishable from early Neanderthals. Could it be…? Yes it could, Hershkovitz says, possibly a member of the group ancestral to Neanderthals that stayed in Africa. Maybe he’s Species X.

Whatever spot X marks, clearly Neanderthals (and Denisovans) and humans mixed time and again. How did we get along?

“There was something about them,” Hershkovitz speculates dreamily from the bowels of another mixed-hominin cave in central Israel. “They seem to have always stirred our passions.”

Or vice versa, maybe pudgy light-haired Neanderthals with their barrel bodies and rangy, dark-complected moderns with their fancy chins were into interspecies kink – anyway, this meeting would beget two groups: Homo sapiens with pre-Neanderthal traits and pre-Neanderthals with sapiens traits.

The Neanderthals had Yabrudian stone tool technology, but the sapiens brought improved Mousterian manufacturing techniques, which the local Neanderthals embraced. How much better was Mousterian than Yabrudian anyway? “Like a Mercedes versus a buggy,” Hershkovitz says.

Oh. The upshot is that if one finds only tools one can’t say the site was sapiens or Neanderthal because of the interaction; only bones can tell. What is their story?

The charm offensive

The classic view of Homo sapiens is aggressive arch-predator, competitive and deadly to other human species. The earliest recognized race war from 13,000 years ago featured horrifying weapons that archaeologists suspect were intended to terrorize and maim, including what may have been the world’s first mace. But what about earlier?

Hershkovitz for one rejects the hypothesis of the horrible hominin.

“We say no,” he says. Neanderthals and Homo sapiens are recognized to have shared Europe for a few thousand years and in Asia, Denisovans and humans also shared space for at least as long. “Not only didn’t the other species disappear, in Israel they cooperated and coexisted for 100,000 years,” he adds.

Ergo, how did they get along? Really well, he thinks. The two populations developed not only biological relationships, but social ones too.

Note that your inner Neanderthal isn’t from any of this. The ancients of Israel 200,000 and 140,000 years ago may have been kissing not hissing, but all non-Africans alive today have Neanderthal ancestry from an interbreeding event 50,000 years ago. All other lineages died out.

So competition isn’t in our blood? What is? How did we remain the last hominin standing?

We became a more social animal, capable of forming large groups, Hershkovitz suggests. Numbers count. Humans experienced self-domestication.

When one domesticates an animal, it changes. Sheep got dumb, cows give more milk and the less we say about farm-grown chickens the better. We selected for friendliness in the dog and in ourselves and thusly changed, our aggressive archaic brow ridge receding, our broad face becoming less threatening. Neanderthals did not undergo a parallel self-domestication experience, and big groups of humans may have absorbed the small groups of Neanderthals and that was that. We didn’t bully them into capitulation, we charmed them.

No evidence of mass murder has been found from the time. No signs of violence on the bodies we have found, of which there are dozens, Hershkovitz points out.

Then about 100,000 to 80,000 years ago, the Land that would become Israel emptied. No human fossils have been found from that time. That could be bad luck or the result of population bottlenecks following the Toba super-eruption in Indonesia 74,000 years ago, creating volcanic winter, which is thought to have brought global humanity (such as it was at the time) to the brink. Not only did our local Neanderthals and humans vanish; so did local hippos, Hershkovitz adds. Then about 70,000 to 60,000 years ago there was a massive migration out of Africa, the humans met Late Neanderthals en route and mixed with them possibly in Iraq, and the rest is prehistory and history. It seems we really could not resist one another.